Revolutionizing Motor Racing with Hybrid Innovation

Decades of Pioneering Motorsport Innovation

Explore Astauto’s cutting-edge contributions to racing car design and development, where innovation meets race car design and engineering experience.

Advanced Aerodynamics

Revolutionizing racing with state-of-the-art aerodynamic evaluations to enhance speed and performance.

Holistic Vehicle Dynamics

Integrating advanced simulation tools to optimize vehicle dynamics for superior track performance.

Our Legacy in Motorsport Excellence

With Sergio Rinland 50 years’ experience in Motorsport Worldwide, Astauto is in a position to assist racing car manufacturers and racing teams with a holistic approach when it comes to design and develop racing cars.

Astauto uses state of the art simulation solutions and collaboration with partners to cover every aspect of a racing car. If we don’t know, we know who does!

Our Expertise in Racing Car Design

Comprehensive Vehicle Simulation

Utilizing industry-leading software to simulate and analyze vehicle performance, ensuring optimal efficiency and drivability.

Aerodynamic Design Solutions

Utilizing advanced simulation tools, we conduct holistic simulations to evaluate different aerodynamic solutions to reduce wind tunnel and track testing costs.

Powertrain Development

Designing and validating powertrain systems through rigorous simulation, delivering high-performance specifications.

Project Management & Collaboration

Astauto can assist in managing complex projects with a collaborative approach, integrating the latest technologies for seamless development and execution.

Collaborative Excellence in Racing Innovation

Astauto has forged strong partnerships with leading racing teams and manufacturers, driving innovation through collaborative projects. Our expertise in design and engineering has enabled us to work closely with industry leaders to create cutting-edge racing solutions. These partnerships have resulted in groundbreaking advancements in vehicle performance and technology, setting new standards in the motorsport industry.

Our collaborative approach with top-tier racing teams and manufacturers has led to the development of revolutionary racing cars. By combining our technical expertise with the unique insights of our partners, we have achieved remarkable outcomes that push the boundaries of speed and efficiency.

Showcasing Our Racing Legacy

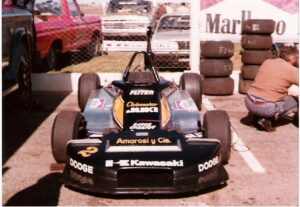

Berta Dodge F2 (1979 and 1980)

Berta Dodge F2 (1979 and 1980). This was Rinland’s first Argentine national championship development. This particular car was driven by Enrique Benamo to three victories in 1980 plus numerous pole positions. Only the fragility of its engine prevented Enrique to score more wins. Notice the aluminium side pods; this was the first Ground Effect car in Argentina.

PRS 82 Formula Ford 1600 (1982)

First car design in England by Rinland; it was completed shortly after his arrival to England from Argentina. This PRS 82 competed successfully in England as a factory car; in Austria, Germany and Benelux countries with Walter Lechner Racing; and in the US with Chip Ganassi as a driver.

PRS 83 Formula Ford 2000 (1983)

This car was a full ground effect car, with bodywork in fibre glass five-component glass-fibre enveloping the whole space frame chassis. This PRS 83 was campaigned by PRS in England and Walter Lechner Racing in the European and German FF 2000 championship.

Ralt Formula 3 (1983)

Rinland spent a short spell with Ralt in 1983, working in the drawing office designing components for the F3 and F2 cars. That was the year Ayrton Senna and Martin Brundle race down to the wire for the British F3 championship. In F2 Ralt was dominant with Dr. Jonathan Palmer and Roberto Moreno.

Ralt Formula 2 (1983)

Rinland spent a short spell with Ralt in 1983, working in the drawing office designing components for the F3 and F2 cars. That was the year Ayrton Senna and Martin Brundle race down to the wire for the British F3 championship. In F2 Ralt was dominant with Dr. Jonathan Palmer and Roberto Moreno.

RAM 03 (1985)

The RAM 03 was co-design by three engineers – Gustav Brunner, Tim Feast and Sergio Rinland. Running with Hart Turbo engine and Pirelli tyres, the car suffered a lack of development due to budget shortfalls and also a number of engine problems Rinland specialized on composite materials, designing and specifying the chassis and bodywork and still rates the RAM as one of the best looking of his career.

Williams F1 FW11 (1986)

At Williams, under Patrick Head, Rinland continued to accumulate knowledge and experience. He was responsible for the monocoque and front suspension of the race-winning FW11, with Brian O’Rourke as the composites Engineer and Head as Chief Designer. Rinland also engineered Nigel Mansell during the winter testing season and in the first race of 1986.

Williams F1 FW11 (1986)

At Williams, under Patrick Head, Rinland continued to accumulate knowledge and experience. He was responsible for the monocoque and front suspension of the race-winning FW11, with Brian O’Rourke as the composites Engineer and Head as Chief Designer. Rinland also engineered Nigel Mansell during the winter testing season and in the first race of 1986.

Brabham BT56 BMW (1987)

This car co-designed by Dave North, John Baldwin and Sergio Rinland, with Rinland responsible for the monocoque, bodywork and front suspension. A good car and a fantastic team. Rinland also engineered Andrea De Cesaris at races, with Charlie Whiting engineering the other Brabham for Riccado Patrese. 1100HP and Pirelli tyres.

Brabham BT56 BMW (1987)

This car co-designed by Dave North, John Baldwin and Sergio Rinland, with Rinland responsible for the monocoque, bodywork and front suspension. A good car and a fantastic team. Rinland also engineered Andrea De Cesaris at races, with Charlie Whiting engineering the other Brabham for Riccado Patrese. 1100HP and Pirelli tyres.

BMS Dallara 188 (1988)

Benefiting from the Brabham sabbatical of 1988, Rinland operated out of Italy, at Dallara, to pen this car as Chief Designer. Powered by a Cosworth DFV, it was underpowered compared with the turbo cars, but it was nonetheless a simple, logical car that did its job for a new constructor and a new team. It was also the first car to use a double end plate front wing, developed in the ¼ scale Dallara wind tunnel. Alex Caffi did a competent job and proved to be an ideal driver for that kind of enterprise.

Brabham BT58 Judd (1989)

Rinland return to Brabham as Chief Designer at end of 1988. Gerard Crombac described the BT58 as a “Très jolie voiturette”, a nice compliment for a car that worked very well when the Pirelli tyres match the tracks – at Phoenix, Monaco, Suzuka and Spa, for example. Stefano Modena finished 3rd at Monaco with the BT58 and Martin Brundle 5th.

Brabham BT59 Judd (1990)

This car was a development of the BT58, with the narrow-Vee Judd engine and the prototype gearbox that would be developed for the BT60; this was a three shafts transverse unit. A lot of the BT60 components and ideas were tested in the BT59.

Brabham BT60 Yamaha (1991)

This was a very good car, hampered by a new engine – the five valve Yamaha V12. That engine was relatively long and heavy, which made the car difficult to balance from the weight distribution point of view, as well as placing a premium on cooling. The drivers were Martin Brundle and Mark Blundell. The aerodynamics were the results of a yearlong research programme by the chief aerodynamicist, Hans Fouche and Rinland, hence the shapes and curves. Part of the research was a 3D mapping of pressures, velocities and flow direction in the wind tunnel; this took several weeks whereas a similar body of data today could be obtained by CFD in only few hours. The gearbox was designed together with Alec Stokes, of BRM and Lotus fame, and built by Xtrac; it was a three-shaft transverse unit, as narrow as a longitudinal gearbox of that period and very compact.

Fondmetal GR02 – Cosworth HB (1992)

Rinland rates the Fondmetal as probably his best car to date because of the way it was conceived and for its innovative aerodynamics and design ideas. It was the first project for Astauto Ltd By December, 1991, Brabham closed down and effectively moved to Milton Keynes. At this point Rinland decided to open an office for his consultancy company, Astauto Ltd, in Tolworth, Surrey, England, employing many of the old Brabham personnel. The company also rented from Yamaha the Brabham wind tunnel as well as some shop floor space for a model shop and prototype assembly area. By Christmas Astauto had our first client – Fondmetal F1 team. By January 1st the new team was flat out designing the GR02 and also working on an update of the GR01 to enable the race team to start the season with that car and the HB engine. After spending two weeks assembling the car at the Fondmetal workshop in Italy, the GR02 was by mid-May running at Fiorano, at Ferrari’s private test track. In the process, two wind tunnel models have been built in record time and more than 200 hours had been clocked up in the wind tunnel itself.

Fondmetal GR02 – Cosworth HB (1992)

The car debuted in Montreal qualifying 18th; at Silverstone few weeks later, the new Fondmetal a great seventh place due only to the team’s inexperience at the pit stops. By Monza, its last race, the team stopped due to lack of finance. The GR02 was mechanically much simpler than the Brabham BT60, it was designed with the user in mind; it had a simple two-shaft Xtrac gearbox, which shared internals with Lotus, and dual shocks front and rear. The aero was more adventurous, featuring side channels that were only adopted by other teams, including Ferrari, as late as 2002! Today these channels are common practice. The front wing was also the result of a lot of thought: although the curvy main plane and flaps looks normal enough by today’s standards, they were a novel feature in ’92. Rinland manage the air flow around the front wing and allowed it to affect the floor and diffuser in the correct manner. It worked, too, and both Gabriele Tarquini and Eric van der Poole will today say that the GR02 was the best racing car they ever drove. This is a nice compliment for a car which was design and build in record time for a team that was well under-budget and under-resourced.

AAR Eagle IndyCar (1993-1995)

After the closure of Fondmetal, Rinland flew to California to work the American racing icon, Dan Gurney, at All American Racers. At that time, AAR was working on a feasibility study for Toyota’s participation in Champ Car. Juan Manuel Fangio Jr and PJ Jones (Son of Parnelli Jones) were the test drivers, AAR bought a Lola in which to run the new Toyota engine while the new car was being designed, in different versions, for two different engines.

Rosberg Opel Calibra DTM (1995)

Back in England, and after a short spell as a consultant for the new Forti F1 team, Rinland was invited by Keke Rosberg to take up a position with his DTM Opel Team as Technical Director. The challenge of something different was irresistible, so Rinland completed the 1995 season in DTM. The 4WD Opel Calibra was powered by a Cosworth prepared V6 engine and used an Xtrac transmission system.

Bowman BC5 FF2000 (1995)

Between the end of the 1995 DTM season and an exciting new F1 project at Benetton, Vic and Steve Holman asked Rinland to design an FF2000 for the US market. This was completed in a short period of time and virtually as a single-man project. This stands as the last car on which Rinland design every piece himself, for F1 was expanding rapidly and a team of more than 20 engineers would quickly become the norm. The car was very competitive “out of the box” in the ovals and road courses and was run by Highcroft Racing, a race team owned by Duncan Dayton, who is today a front-runner in ALMS.

Benetton F1 (1996-1999)

From January 1996 to December 1999, Rinland worked at Benetton Formula as a Composites Engineer. There he was a major part of the team which designed the Benetton B197, B198, B199 and B200.

Sauber C20 (2001)

At the end of 1999 Sergio was head-hunted by Sauber to join as Chief Designer .The C19 was nearly finished when Rinland arrive in December, so he was initially charged with its development; then, in April/May 2000 he and his design team started work on the new C20. The Sauber C20 had several novel ideas including the twin-keel front lower wish bone attachment, designed to improve the air flow to the underfloor. This system was subsequently adopted by Mc Laren’s Adrian Newey. Mechanically it feature a very neat gearbox and oil tank, very efficient systems. Attention to detail and weight saving was the prime objective, but the C20 also achieved a very favourable weight distribution for the Bridgestone tyres of the day. All this translated into a well-balanced, high-grip car to drive that allowed Kimi Raikkonen and Nick Heifeld to put in several very creditable performances during the 2001 season, culminating in fourth place in the World Championship – a huge achievement for a middle-of-the-field team.

Arrows A23 (2002)

Rinland joined Arrows in September, 2001. The A23 was being designed upon his arrival, and with most of the mechanical package carried over from the A22, a big effort was devoted to the aerodynamics – particularly on developing the twin keel concept of the 2001 Sauber. Unfortunately, lack of funds prevented any serious developments. The problem was so severe that Spa, in September, actually marked the last appearance of the A23, although this did become the base of the Super Aguri Formula1 effort in 2006, proving that its basic design was still valid four years later!

PEUGEOT 307 BTCC – 2003

After the demise of Arrows, Astauto developed the Peugeot 307for the British Touring car Championship. This was Rinland’s first closed-car design.

Cheever Racing Dallara IRL (2004)

After the Indy 500 2003 Eddy Cheever commissioned Astauto to develop the Dallara car for the oval-based Indy Racing League. A new suspension package was designed, saving weight and increasing its installation stiffness as well, as many aero and vehicle dynamics developments. In the first race of 2004, at Homestead, the Red Bull Cheever Racing cars were in the front row. Astauto’s contract lasted for 12 months, covering the Indy 500 of 2004.

Aston Martin DBR9 GT1 (2006-2007)

During 2006 and 2007 Rinland worked as Technical Director of Team Modena, campaigning a DBR9 in the LMS and Le Mans 24 Hours. The driver line-up included Antonio Garcia, David Brabham, Nelson Piquet Jr, Christian Fittipaldi and Jos Menten and the Le Mans and LMS races are considered by Rinland to be the most enjoyable events in motorsport today, combining reliability, speed and strategy at the highest level.

Epsilon Euskadi EE1 LMP1 Judd (2008)

When Rinland joined this Spanish-based company, in October 2007, the EE1 was under construction and its program was much-delayed. His first priority was to get the car on track. This was duly achieved at Paul Ricard in February 2008, but at that point it was realized the EE1 was not an easy car and needed a big development program to be both competitive and reliable. By the Silverstone 1000Km (the last race) the EE1 was faster than the Lola’s and very close to the third Audi- another massive achievement. During 2008 Rinland assembled a strong engineering team and created the EE2 design, a car that would carry over only the windscreen and top half of the doors from the EE1. The simulation showed a huge performance improvement and all available data indicated that the car would be both more reliable and user-friendly for the drivers and mechanics. Sadly though, the EE2 never saw the light of day: lack of finances prevented Epsilon to build it and race it in 2009.

Berta Dodge F2 (1979 and 1980)

PRS 82 Formula Ford 1600 (1982)

PRS 83 Formula Ford 2000 (1983)

Ralt Formula 3 (1983)

Ralt Formula 2 (1983)

RAM 03 (1985)

Williams F1 FW11 (1986)

Williams F1 FW11 (1986)

Brabham BT56 BMW (1987)

Brabham BT56 BMW (1987)

BMS Dallara 188 (1988)

Brabham BT58 Judd (1989)

Brabham BT59 Judd (1990)

Brabham BT60 Yamaha (1991)

Fondmetal GR02 – Cosworth HB (1992)

AAR Eagle IndyCar (1993-1995)

Rosberg Opel Calibra DTM (1995)

Bowman BC5 FF2000 (1995)

Benetton F1 (1996-1999)

Sauber C20 (2001)

Arrows A23 (2002)

PEUGEOT 307 BTCC – 2003

Cheever Racing Dallara IRL (2004)

Aston Martin DBR9 GT1 (2006-2007)

Epsilon Euskadi EE1 LMP1 Judd (2008)

What Our Motorsport Clients Say

“Sergio, I always feel a deep sense of nostalgia when I think about the time we spent together in Formula 1. We were young (it was 1988), full of enthusiasm and with limited resources, yet under your technical leadership, we designed and built a car in a short time that allowed Scuderia Italia and Alex Caffi to hold their own with dignity against numerous experienced competitors. Then our paths diverged, but I will always be grateful for the contribution you made to the growth of Dallara Automobili, and I am pleased to see that your expertise continues to enable you to successfully tackle new challenges.”

Gianpaolo Dallara

Dallara Automobili

“Over the years, AVL has been proud to collaborate with Astauto, a dedicated and innovative user of our simulation software. Their invaluable feedback and commitment have significantly contributed to the evolution and refinement of our tools, ensuring they meet the highest industry standards. Astauto’s proactive approach to leveraging our technology has not only enhanced their own projects but has also played a key role in advancing simulation capabilities for the broader Automotive and Motorsport engineering community. Together, we have fostered a relationship rooted in mutual growth, technical excellence, and shared vision for innovation.”

AVL List GmbH

“We first had the pleasure of working with Sergio when he was at Brabham in 1989 and 1990, supplying Judd EV 3,5 litre V8 engines for the 2 Brabham BT58 cars driven by Martin Brundle and Stefano Modena. Whilst it was a difficult time for the team Sergio had in fact designed an excellent F1 car which achieved a 3rd place at the Monaco GP that year and further enhanced his reputation as a car designer. A further collaboration was in 2008 for the Epsilon LMP car which sadly never came to fruition but was as ever a pleasure due to Sergio being responsible for the engineering and design, displaying a high level of competence and friendly liaison throughout.”

John Judd

JUDD Power

Case study: AIM Le Mans Project

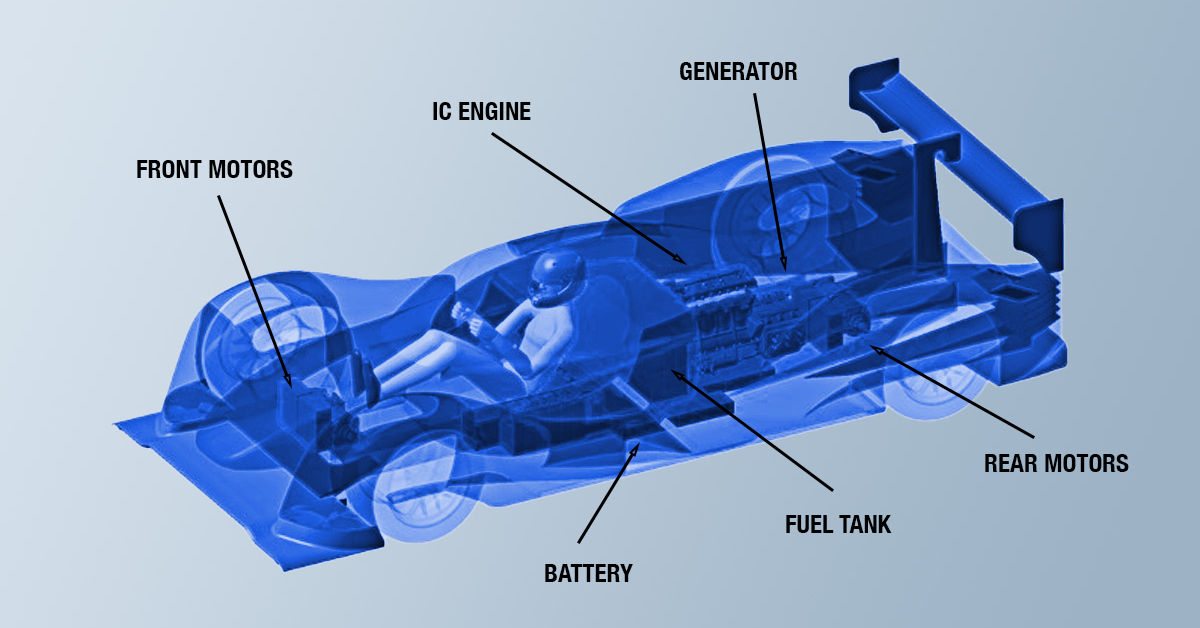

LMH Prototype

Le Mans Hypercar Prototype

The Brief

In 2018, the ACO and FIA announced the introduction of the new LMH (Le Mans Hypercar) Sport Prototype category, set to debut in 2021. This initiative aimed to reduce costs and attract more manufacturers. A few years later, a Japanese second-tier automotive supplier decided to showcase and promote their components by creating their own LMH team.

With plans to debut in 2022, this OEM supplier commissioned Astauto to conduct a feasibility study—assessing the technical and financial requirements for building the cars and participating in the WEC championship with their own LMH entry. Additionally, Astauto was tasked with producing and providing technical support for the proposed WEC team.

Deliverables

After a three-month program, Astauto delivered:

- Performance target estimations: Based on a fully modeled and developed LMH car simulation, incorporating initial targets for aerodynamics, vehicle dynamics, and powertrain specifications.

- BoM creation and PERT chart: A comprehensive Bill of Materials and PERT chart for the design, development, and construction of the LMH car, informed by our experience with LMP1 design and production.

- Budget creation: Utilizing the BoM and partner quotations, we outlined five distinct racing scenarios with corresponding budgets:

- One-car team – 2 Races + Le Mans

- Two-car team – 2 Races + Le Mans

- One-car team – Full WEC Championship

- Two-car team – Full WEC Championship

- Two-car team + spare car – Full WEC Championship

Our approach

Astauto’s strategy for this project comprised the following steps:

- Study of LMH regulations and creation of the Specifications Book: The LMH regulations, introduced in 2021, were based on a concept proposed to the ACO by Sergio Rinland in 2010. Unlike traditional approaches, this concept focused on regulating performance outcomes—such as power output, aerodynamic drag, and downforce—rather than prescribing vehicle design details.

- Power is measured via torque and RPM at the driveshafts, while drag and downforce are homologated through standardized wind tunnel tests. Homologated 3D designs are submitted to the FIA for verification, with random checks during scrutineering at events.

- Although the initial downforce and drag targets seemed achievable based on our LMP1 experience, maintaining maximum efficiency (lift-to-drag ratio) across various speeds and ride heights presented a significant challenge. Our first step was launching a CFD program to evaluate these constraints.

- For power, while achieving peak outputs appeared straightforward, the challenge lay in designing a combined rear ICE and front MGU system capable of consistently operating at maximum allowed power.

- Initial aerodynamic design and CFD program: The project’s Specifications Book outlined ambitious aerodynamic targets. These targets guided the aerodynamic simulations to predict the vehicle’s performance across Le Mans and other WEC circuits.

- ICE and MGU torque-power curve specifications: LMH regulations defined a power curve at the wheels with specified minimum and maximum tolerances. Our simulation model incorporated an ICE with this torque curve and a control system to adjust output when the front motors were activated.

- Simulation program to assess target performance: Using AVL VSM simulation software, we conducted detailed simulations to establish performance targets for the vehicle’s key parameters as outlined in the Specifications Book.

Accelerate Your Racing Ambitions

Unlock the full potential of your racing projects with Astauto’s cutting-edge design and development services. Our team of experts is ready to collaborate with you to create innovative, high-performance racing cars that stand out on the track. Reach out to us today and let’s drive your vision forward.